he term ‘consort organ’ is one that is gradually being more widely adopted within the organ literature to describe a particular type of English seventeenth-century chamber organ that exhibits very specific features and that was developed for specialised musical uses. I hope that my research will help to clarify this definition and illuminate these uses more clearly, particularly among those musicians (both organists and string players) who play the English string consort repertoire today.

he term ‘consort organ’ is one that is gradually being more widely adopted within the organ literature to describe a particular type of English seventeenth-century chamber organ that exhibits very specific features and that was developed for specialised musical uses. I hope that my research will help to clarify this definition and illuminate these uses more clearly, particularly among those musicians (both organists and string players) who play the English string consort repertoire today.

A full organological description of the consort organ may be found in the first chapter of my thesis, but the following is a brief introduction. For an overview of the many and important differences between it and the modern types of continuo organ often used today, scroll down to the table at the bottom of the page.

Readers may, incidentally, wonder at the use of ‘England’ and ‘English’ throughout this site, rather than ‘Britain’ and ‘British’. The reason is that, so far, only two references to domestic organs from the seventeenth century have been identified originating in Scotland, and none at all in Wales. The consort organ seems therefore to have been a distinctly English phenomenon.

Origins.

The consort organ developed from the technology found in the smaller, usually wooden-piped and often movable positive organs used in the sixteenth-century English church. These contrasted with the larger, metal-piped and permanently fixed great organs that were used alongside them. For a reconstructed example of a mid-sixteenth century positive, see the ‘Wingfield’ organ produced for the Early English Organ Project, based on the remains of an early sixteenth century soundboard found in Suffolk.

The positive organ also evolved into the ‘chair’ or secondary division found in the double (i.e. two-manual) church organs that began to appear in the early seventeenth century. The stoplists of consort and chair organs thus shared a number of features, and the same builders often made both types.

Whilst the church organ evolved throughout the century, the secular consort organ remained remarkably unchanged in its essential design until it eventually fell from favour in the 1690s.

Types of consort organ

Four types of consort organ may be identified. Each type has general parallels in the contemporary organ-building traditions of other European countries, with the important difference that the tone quality and usage of the English instruments were significantly different in several ways.

The claviorgan is a combination of a plucked-string keyboard instrument with an organ. It originated in the fifteenth century and was used in England into the first few decades of the seventeenth century, after which it was generally superseded by the table and chest types. The 1579 example by Theeuwes, made for Farningham Manor in Kent and now in the V&A, is the sole surviving English example.

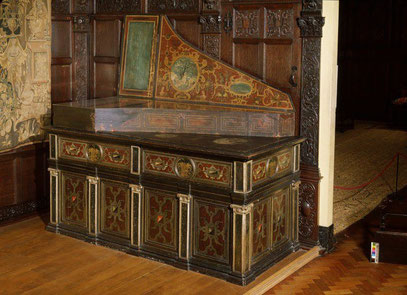

The chest organ resembled a modern box continuo organ. These do not appear to have been common in England although they appear more frequently on the continent. The organ was played standing up, or on a high stool, in the manner seen in contemporary Dutch paintings of virginals. Only one English example, the c1600 organ at Knole House, Kent, is extant. It was once associated with the 1st Earl of Dorset’s domestic musical establishment that boasted 11 resident musicians, including singers, violists and lutenists.

Table organs had their pipes and bellows in a case that stood upon a table or supporting open framework. Many had doors that could be closed to protect the instrument so that it resembled an everyday cupboard. In the turbulent years of the Civil Wars, it could be an advantage to disguise the instrument, with its royal associations, from hostile eyes.

The organ now at Historic St Luke’s, Smithfield, Virginia is a particularly fine example of a table organ. It was bought by the L’Estrange family of Hunstanton Hall, Norfolk in 1630 for the very cheap sum of £11 (was it second-hand, and could it therefore predate 1630?). The L’Estranges were fine viol players; they employed Thomas Brewer as their organist and John Jenkins as a composer in residence, and much of the music written for this organ is still extant.

Photo courtesy of TripAdvisor

Cabinet organs resemble table organs, but have enclosed casework in their lower half that often contains the bellows. This type represents the most frequent survivors. A particularly lavish and early example is preserved at Hatfield House, Hertfordshire. A later example is the c1680 instrument possibly by Bernard Smith in the Russell Collection, Edinburgh.The front pipes of cabinet organs appear to be gilded metal but, like the inner pipework, are usually made of wood. They are remarkably compact and, whilst not being portable as such, were able to be disassembled and re-erected with relative ease.

Compass, pitch and temperament

An important difference between church and secular organs was that the former were transposing instruments in F (- i.e. the C key played a pipe sounding the F below), whereas consort organs were pitched in C. The most common keyboard compass was C AA D-c3 (i.e. the bottom C# key played a pipe sounding A below). All but one of the extant consort organs has a single manual, and none have pedals.

A point to note is that the majority of consort instruments were pitched higher than the modern concert pitch of a440Hz: the surviving evidence indicates a pitch trend rising from just above a440 in the 1630s to around a485 by the 1680s. Some organs were pitched higher even than this, and not a single one of the extant instruments from which reliable data can be extracted was pitched as low as the ‘Baroque’ pitch of a415 widely used by string consorts today. This fact alone has important implications for modern-day viol players in this area of the repertoire.

Whereas many continental and church organs used various versions of meantone temperaments at this period, there is evidence to suggest that English consort organs used a much more versatile tuning – not quite equal temperament, but something approaching it – to accommodate the adventurous tonality found in consort works by composers such as Jenkins and Lawes. Thus, in the English consort repertoire, the problems of the disparity between meantone keyboard temperaments and flexible viol tunings that have vexed peformers for many years in the modern age were not actually an issue for seventeenth-century musicians.

Pipework, tone quality and specifications

The main distinguishing feature of the consort organ was the almost ubiquitous use of wooden pipework. This was narrowly-scaled with low cut-ups (mouth heights) to give a quiet but harmonically very rich sound that resembles the sound of viols in several respects . This type of voicing required great skill to achieve successfully, and was evidently essayed to achieve a close blend in tone between the organ and strings in consort works.

Specifications varied remarkably little over the course of the century. The basic provision was Stopped Diapason 8, Principal 4 and Fifteenth 2, to which were often added an Open Diapason 8 (usually treble compass only for space reasons) and a two-rank mixture. The Open Diapason was an important and characteristic feature of these instruments that was highly useful in string consort works. The gentle tone of the upperwork meant that the 4’ and 2’ stops could also be used freely in conjunction with the strings, which is not always possible with modern organs.

Stops were often divided into treble and bass halves. There is no obvious use for these in the solo organ repertoire of the Stuart period: divided keyboards were not specified in either the contemporary English virginal or organ repertoire, and they do not allow allow the performance of the works for two-manual double organs as the individual manual parts in these pieces frequently cross over the divide. Instead, the main reason for this feature appears to have been to enhance the organ’s role in interacting with the strings in consorts. The dividing point corresponded with the c string of the treble viol until about 1650, and with the d string of the violin when that instrument became more popular in consorts after the Restoration. A different registration in the right hand could be used to strengthen the relatively weak tone of the treble viol in consorts, or to emphasise the melody line in the popular dance-based pieces with their polarised treble-and-bass texture.

Musical usage

The principal use of the consort organ was in instrumental string consort music. This role began to emerge in the late sixteenth century, and found maturity in the fantasia suites of Coperario and Gibbons, based at the court of Prince Charles, in around 1610-1620. The pedagogical influence of these composers, combined with the fashionable influence of the court, saw string consorts with organ gain popularity within an interlinked network of aristocratic households in the orbit of the court during the reign of Charles I, from where it spread to lower levels of the nobility as the century progressed. The court repertoire was disseminated to the provinces, and became a popular pastime for those amateur musicians who had the means to buy an organ.

The organ often doubled or shadowed the string parts, particularly in sources prepared for amateur players, but in many works it took an independent, obbligato role without which the texture was incomplete. The sources make it clear that the organ was the preferred instrument in much of this repertoire, even though the harpsichord, theorbo, harp and lyra viol all fulfilled similar roles in other types of work. After the Restoration, continental-style continuo techniques became more common, particularly among professional players. From the early works onwards, organists were expected to improvise parts from scores or figured and unfigured basses, to extemporise divisions, to fill out skeletal organ parts and often to direct the ensemble.

Consort organs also found an important role in the domestic devotional vocal music popular in many households. They were also employed in the Jacobean theatre, cathedral and university choir schools, music meetings in London, Oxford and Cambridge, and also in the popular music houses or taverns that flourished in London during the Interregnum.

Differences with the typical modern continuo organ

The differences between the consort organ and the vast majority of modern continuo organs used in present-day performances are significant and numerous. These differences impact on the aural effect of the music, and often prevent the modern organ from fulfilling the varied roles expected of the consort instrument. It is common today to hear just a single stop used unremittingly throughout a concert or recording, its tone colour contrasting strongly with the strings. The consort organ, by contrast, provided a series of dynamic levels and stops of varying pitches all of which were carefully designed to blend with the strings, producing colour and variety and yet, at the same time, maintaining a characteristic homogeneity of ensemble. It was this ability that enabled the organ, as Thomas Mace put it in 1676, to fulfil a role of ‘Evenly, Softly, and Sweetly acchording to all’.

The differences between the modern continuo and consort organs are summarised in the table below. To find out more about how the techniques required of seventeenth-century organists differed from those playing from a modern editorial part today, see the entries on the page on performance practice.

| Consort organ | Continuo organ |

| Pitch rose from a mean of a440 in c.1630 to a465 by c.1670 and a494 by c.1700 | Transposable between a415 and a440, occasionally a430, and more rarely a465 |

| Something close to equal temperament in many cases, or otherwise mild modified 1/5 or 1/6 comma meantone | Variable depending on context, but often ¼ comma meantone, or tunings based on 18th century continental formulae |

| Compass typically C AA D-c3 | Compass typically C-f3, g3 or a3; no AA |

| Keyboard division b/c (before c.1650) or c/c# (after c.1650) | When provided, b/c |

| 8ft treble Open Diapason common | 8ft Open Diapason very rare |

| 4ft Principal always provided | 4ft Principal often omitted in favour of a 4ft Flute for reasons of space |

| Low-pitched Mixture, typically 12.17 | High-pitched upperwork, usually separate 19 and 22 ranks |

| All wooden pipework | Mixture of wooden and metal pipework, the latter especially for principal-toned stops |

| Narrow scales, based on empirical methods | Wider scales, based on mathematical formulae |

| Very low cut ups | High cut ups |

| Relatively high wind pressure | Very low wind pressure |

| Pipework regulated at the toe with wedges | Open-toe voicing |

| Voiced with rich harmonic content to blend with strings | Prominent emphasis on 2nd harmonic for 8fts, ‘nasal’ or ‘flutey’ tone colour common |

| Little starting transient to pipe speech | Prominent ‘chiff’ to pipe speech |

| Voicing style evolved from 16th century English positive organ tradition | Voicing style usually based on 17th or 18th century models, often continental, often liturgical |

| Upperwork of moderate dynamic output, used to enrich tone colour not overall volume | Upperwork louder as stop pitches ascend, used to increase overall dynamic volume |

| Dynamic output designed for use with small ensembles in small, often domestic, spaces | Dynamic output of upperwork designed for use with larger ensembles in concert halls and churches |

| Flexible hand or foot blowing by player or an assistant | Inflexible electric blower |

| Pipes speak at seated head height | Pipes speak near floor level |